As many say in the beekeeping world, ask ten people about something, and you’ll get eleven different answers. I don’t think that’s entirely true, but beekeeping is undoubtedly a ‘broad church.’ A common way to start beekeeping in the UK is to buy a nucleus colony; a small but perfectly formed colony of bees in a small box. Nucs comprise full-sized frames, all drawn out, with bees, brood and stores. All you have to do is drop the frames into a beehive, add further frames of comb or foundation, and away you go.

Nice Package

As I understand it, in the States, people tend to favour package bees over nucs. The absence of frames and brood may bring down the cost, and reduce disease risk to some extent, but problems can arise because it is not a balanced colony. A package of bees is more like a swarm, but in some cases, the proportion of nurse bees may be much lower than in swarms. Package bees also have the advantage of working with all shapes and sizes of beehives; shake them in and feed. Mike Palmer once told me that adding a frame of emerging brood a week or two later helps the colony by introducing nurse bees, which may deter their attempt to supersede the queen.

Mrs Walrus

As I have previously described, when Mrs Walrus was editing my book, she realised the income potential of selling nucs and wasted no time in strongly suggesting that I “up my game”. I was considering selling them anyway and got right to it. The nucs I make for sale are on National frames whereas the ones for me are on my prefered Langstroths. Luckily feedback from customers was excellent. I always feel a little sad about letting a nuc go. There is a conflict between keeping the best queens for myself and selling them on; I can hardly sell people poor queens, that would be silly.

The main point of nucs, however, is not to sell them to other beekeepers. I think they are the best way to take mated queens through the winter, so that should I need to replace losses I have them ready to go. They are like a comfort blanket; if I have plenty of nucs on the go, I know I have access to queens, bees and brood at any time.

Recently I spoke to some commercial beekeepers about how they make up nucs. I was primarily interested in ‘getting the biggest bang for my buck’ – making strong nucs from few resources. In the right conditions, it’s incredible how much you make from so little. Here’s what they said:

Michael Palmer

Made earlier in the season, fewer resources are needed. We begin about June 15. At that time, we’re into the main honey flow. We make up a four-frame nuc with two frames of brood (one sealed and one sealed/open), one frame of honey, enough bees to cover those three, plus one frame of foundation. These earlier made nucs will draw foundation in a second story and probably require a third story before the end of July, in preparation for the goldenrod flow.

After the beginning of July, I make them with three frames of brood. This is because our main flow ends mid-July and by the time they are strong enough to draw foundation the flow is finished…so we make them a bit stronger…to imitate how they would look if made earlier.

Many will need a third story, as I said, to stop swarming. The third is mostly comb, and the box goes in between the first two.

Murray McGregor

It depends on the type of bee and the nectar flows. What we do in our area with our bees is:

Up to end June Make up in a poly nuc one bar of sealed brood, one of honey, bees to cover those two frames, foundation frames to fill the box. Feed syrup until the foundation is drawn. After one week return to kill EVERY queen cell, then introduce a mated queen. We get over 90% acceptance. Three weeks after making up the nuc you have 4-5 frames of bees. They can be split into 3 nucs after 4 weeks, and this can continue so from one bar of brood you can end up with nine nucs of bees for winter!

End June to End August As above but start with 2 bars of brood.

Sept/October We use three bars of brood and covered with bees from three different colonies. They get confused and don’t fight. Bees from just two colonies will fight. Introduce the mated queen straight away.

Peter Little

Early on we make nucs up with a frame of brood, a frame of honey and three frames of foundation plus bees. Add a mated queen in a cage and feed 3 litres of syrup. They expand quickly and need to be split in two or three weeks.

The nucs that we sell need to be made up stronger. We use two frames of brood and three of foundation, plus 1 Kg of bees shaken from supers of various hives. They go into a box with a mated queen and 3 litres of syrup; in two to three weeks they are ready to sell. The advantage of using bees shaken from supers (above a queen excluder) is that there is no chance of transferring the queen or drones from the donor hives.

As part of swarm control and general management to keep hives of equal size, we remove a frame of brood from many hives each week. That brood can be used to make up nucs.

So, there you have it. Make nucs! It’s easy-peasy and well worth it.

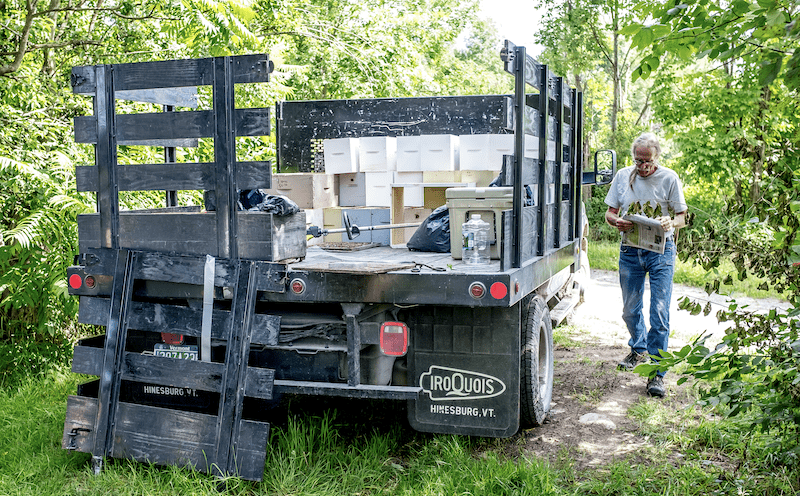

Mike Palmer, French Hill Apiaries, St Albans, Vermont

Murray McGregor, Denrosa Apiaries, Coupar Angus, Scotland

Peter Little, Exmoor Bees & Beehives, Somerset, England