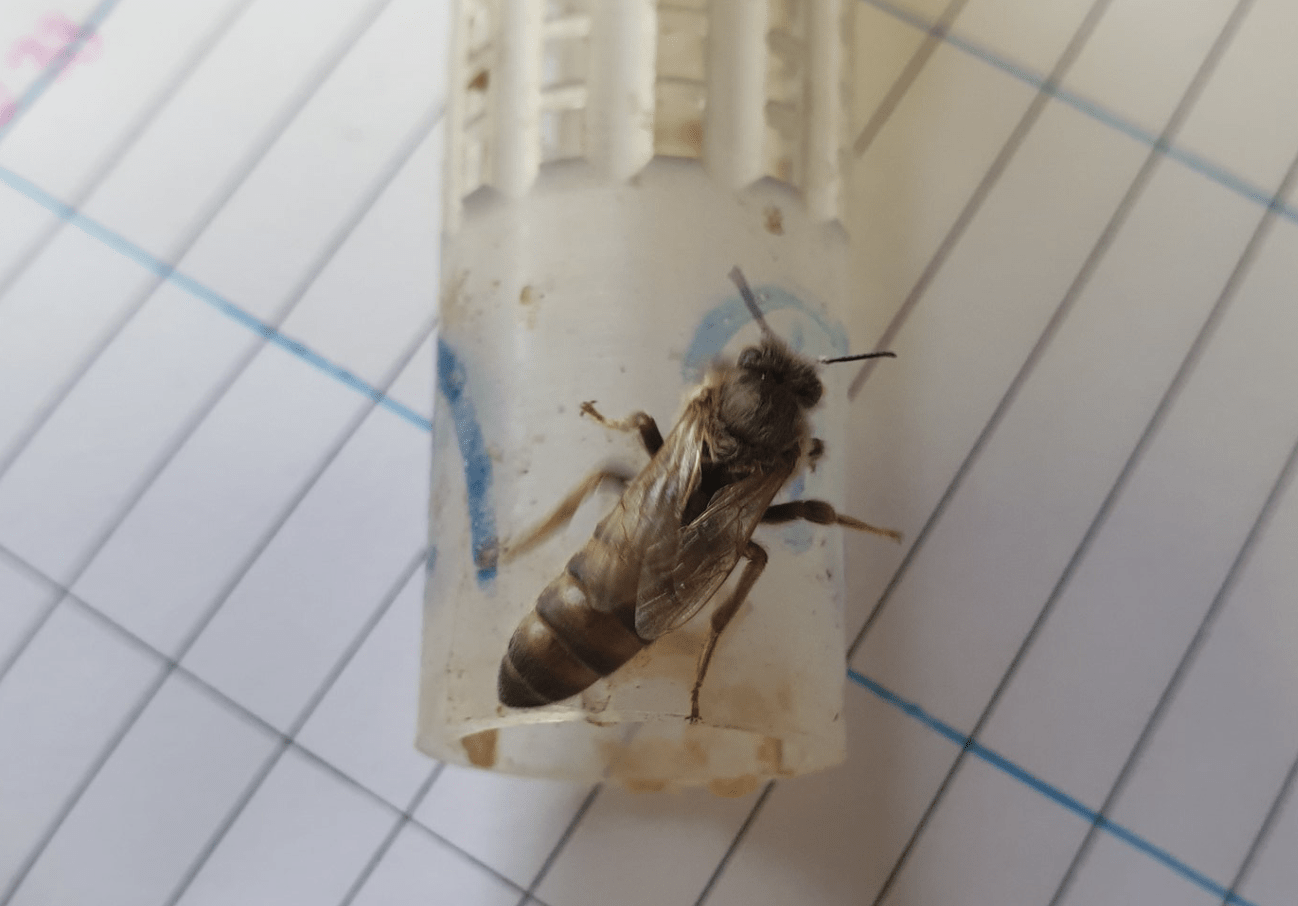

Honey bees have been around a lot longer than humans, and the way they organise their colonies and their lives seems to work very well for them, even if it sometimes seems a little strange to us. They have a system involving three types of adult bee (the queen, workers, and drones), three types of brood (eggs, larvae, and pupae), and an incredible comb structure made of wax that is both lightweight and strong. The only properly reproductive female in a colony made up largely of females is the queen. She is a ‘normal’ female as we understand it; the thousands of other females that do not reproduce are the anomalies as far as most life-forms are concerned. That means that there is a lot resting on the success and quality of a single insect in a colony of 20,000 to 60,000 of insects.

Not a monarch

The term ‘queen’ can be misleading, as she does not reign over her ‘people’ in a hierarchical system. Each component of a honey bee colony is important, and each relies, to some extent, on the other components. Bees are often attributed great intelligence, but my understanding is that they are instinctual creatures, responding in pre-programmed ways (laid down in their DNA) to stimuli. The bees in the hive are in the dark, so smells/tastes and vibrations are the modes by which stimuli are experienced. Outside, on the wing, vision comes into play, but not the type of vision experienced by us.

If any part of the honey bee colony is in control, it’s probably the workers, but not consciously so. There are far more of them than drones or the queen, and they perform the majority of the tasks required. Workers will feed the queen so that she lays eggs, then feed the brood, so the colony can grow. In the Spring, if conditions look promising, they will start swarm preparations, and may build queen cells so that once the swarm has left the parent colony receives the gift of a brand-new queen.

Swarming

Swarming is a natural part of honey bee biology, and one way in which a colony can change its queen. Although bees that are very prone to swarm do not suit my style of beekeeping, I would not want to see it disappear altogether. Each season is different, but if around a third of my bees try to swarm, I think that’s about right. In the wild, in unmanaged colonies, the swarming rate is much higher than this, and it works for the bees. However, for me, a strain of bee that has been selectively bred to have a lower swarming tendency is easier to manage and more likely to produce larger honey crops. Horses for courses, you might say.

Heavy going

There are various ways in which a colony of honey bees, left to its own devices, might change their queen. Swarming is something that happens when the going is good, to continue the equine metaphors. If the colony is healthy and strong, resources are plentiful and the weather fine, why not? But occasionally the going is heavy, and swarming is not on the cards. The main ‘natural’ alternatives are:

1) Supersedure. The bees make one, or occasionally several, queen cells – normally towards the end of the season – and create a new queen even though the old one is still present. Every so often, this can result in two mated queens (mother and daughter) being in the hive for weeks or months. Rather than reproduction, this is about replacing a queen that is defective in some way, and it does not always work out. The newly emerged virgin queen may not be successfully mated. Leaving it until late in the season, when fewer drones are about, adds to the jeopardy.

2) Emergency Queen. In this case, normally because of some calamitous beekeeper activity, the queen is lost or killed, leaving the colony with resources to make a replacement. Of course, with a so-called walkaway split, the beekeeper sets this up by deliberately removing the queen.

Nature knows best?

Despite the oft-repeated cries of “nature knows best” I doubt that this applies at the individual colony level so much. The way nature works, in a Darwinian ‘natural selection’ system, is great for the survival and evolution of the species. The mating biology of honey bees aims for maximal genetic mixing, with multiple patrilines operating within the hive, providing adaptability to changing conditions. However, at a colony level, just dumb-luck can wipe them out, regardless of how excellent or poor the bees are. As a beekeeper, I’m interested in the prosperity of my particular colonies, although I’m obviously keen for the species to continue to thrive.

I see it as part of my job to keep my bees in peak condition, for their benefit and mine. Part of this involves changing the queen when something is wrong, or even suboptimal. Whereas nature may tend to produce small colonies which swarm frequently and vigorously defend the nest, I am after something else. I want gentle bees that are less prone to swarm and sting; bees which build up into a giant workforce capable of bringing in a vast excess of nectar. To this end, I wish to remain in charge of which queens head my colonies, and this inevitably means that sometimes I intervene.

Beekeeper intervention

So, we get to the nub of the issue – the changing of queens by the beekeeper rather than by the bees. I have done a great deal of this, and have tried all sorts of different methods with varying degrees of success. Last season was our most challenging yet in this regard, and it vexes me. Part of the problem that I face is my inability to follow my own advice. I often tell less experienced beekeepers to find something simple that works, and stick with it. Well, I am always messing about and trying new things; it is part of what makes beekeeping so interesting, but not every idea works out.

The crux of the matter seems to be that not all colonies are very welcoming to the new queen that I would like them to adopt. I have had seasons where this has not been a concern, but last season was tricky. Although I make plenty of queens, and often have more than I need, I don’t like to see my efforts wasted. The goal is to remove an old or below-par queen from a colony and get them to accept the queen that I give to them.

Queen issues in 2025

Part of the problem last season was that I was busy with moving house, and in several apiaries I gave them a queen cell rather than a mated queen. For reasons unexplained, about half of the resulting virgin queens were mated, and the rest went missing. Worse still, a proportion of those colonies ended up with laying workers and no worker brood – basically doomed. Even when we gave healthy laying queens, and delayed release using the normal cage with a candy plug, the bees would frequently kill the new queen and try to make their own. And again, sometimes they were not successful – back to the aforementioned ‘virgins not getting mated’ difficulty. Our normally highly reliable push-in-cage method of introducing queens was also far from perfect. I may be painting too bleak a picture, as in most cases we sorted them out before winter, but more colonies were lost than I feel comfortable with.

Having thought about the queen problems of last season, my initial reaction was to consider that next season we will be super cautious and not release newly introduced queens until the receiving colony is hopelessly queenless. Now I’m going cooler on that idea, but I will do some that way and compare results.

Sweet spot

Theoretically, the ideal time to introduce a mated queen to a colony is about 24–48 hours after they were made queenless. Apparently, this is a sweet spot in which the colony is aware that it has lost its queen, but it has yet to fully commit to making a new one. Once they have embarked on making one of their own, the likelihood of rejection of the newly introduced queen is greater.

There is also the matter of stress in the colony. If the weather is good, and nectar is flowing, the bees seem far happier to accept a new queen than when under the stress caused by factors such as low resources, poor weather etc. Being without a queen is obviously stressful, so waiting for them to make emergency cells then removing them all, to produce a hopelessly queenless colony, is really ramping up the stress. That period without a laying queen means no young brood in the hive, which changes the pheromonal landscape, and perhaps increases stress too.

Gold standard

The absolute gold standard, belt and braces, hardly ever fails way to change a queen is to add a nucleus colony to a queenless one. You are not just bringing in a new queen, but a healthy fully functional colony, with brood at all stages, nurse bees, and a queen. I have never had a problem when doing that. This made me recall a method first described to me by Mike Palmer, which he said he would probably use if he had fewer bees and more time. I shall call it the ‘vertical nurse box requeening’ (VNBR) method, and it goes like this:

Vertical Nurse-Box Requeening (VNBR) Method

A requeening method in which all open brood is temporarily relocated above the queen excluder to concentrate nurse bees in a queenless upper brood box, into which a new mated queen is introduced. Once the queen is laying and socially stabilised, the queen-right brood box replaces the original broodnest.

VNBR deliberately creates a nuc-like acceptance environment inside a full production colony, then promotes that unit to become the primary brood nest.

Step-by-step method

Day 0 — Colony preparation

1. Locate and remove the old queen.

2. Identify all frames containing eggs or larvae.

3. Move these frames (with minimal adhering bees) into a second brood box.

4. Leave behind:

• sealed brood

• stores

• supers as present

Critical rule:

No open brood must remain in the lower brood box.

Day 0 — Vertical separation

5. Reassemble the hive as follows (bottom → top):

• Bottom brood box (now queenless, sealed brood only)

• Queen excluder

• Supers (if present)

• Upper brood box containing open brood

6. Reduce entrances if needed; ensure stores, or begin light feeding if no flow.

Biological effect

• Nurse bees migrate upward to care for larvae.

The upper box becomes:

• queenless

• rich in nurse bees

• incapable of emergency rearing beyond this brood

Day 1–2 — Queen introduction

7. After 24–48 hours, introduce the new mated queen into the upper brood box using a slow candy-release cage, placed between brood frames.

8. Close up and do not disturb.

This timing aligns with the best-supported queen-acceptance window in research literature, which shows improved receptiveness after short queenless periods without extended stress (I think).

Day 6–7 — Check for release

9. Inspect the upper brood box:

• Queen released

• Eggs and young larvae present

10. Remove any queen cells (I bet mine make them)

Day 10–14 – Promotion

- Remove the lower brood box entirely.

- Place the queen-right brood box into the primary brood position (on the floor).

- Reassemble supers as required, above queen excluder.

- Shake bees from the removed brood box in front of the hive

I think I will be trying out the VNBR method next season, and would hope to get 90%+ success. Some people seem to be able to get 80–90% success simply dropping in a queen using a candy cage and snapping off the tab after a couple of days, but that was not the case for this walrus last season. It occurs to me that the best time to do this might be during swarm season, before any swarm cells are present, as it could perform a secondary function of preventing swarming.

However, I do want to increase my colony numbers too, so for that, I will be splitting strong colonies in May. I may well follow the method described by Randy Oliver, which utilises oxalic acid to remove almost all the mites as part of the manoeuvre.

Happy New Year to all, and let’s hope for a glorious 2026.

Feel free to add a polite comment!